New paper 🎉🎉 About coherence 🥱💤⁉️

Note: This was first posted as a mathstodon thread, and archived here.

joint work with Nick Gurski https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11261

The title is: Universal pseudomorphisms, [*deep breath*] with applications to diagrammatic coherence for braided and symmetric monoidal functors 🙃😸

Introduction

I've always thought coherence theorems sound boring, but actually they're good! In this paper we take a problem that is hard (coherence for structured functors), do a bunch of really abstract stuff (2-monad theory), and come out with a solution that makes your life* significantly better.

[*Here, "your life" means the part of your life you spend checking diagrams of braided monoidal functors. Or, more generally, pseudomorphisms for algebras over a 2-monad.]

Almost 1/5 of this paper is dedicated to real, genuine examples, and that's what I want to focus on below. I'll say just a bit about the more abstract machinery on which the examples are based. If you've been following along, this is the culmination of my series "weird facts about monoidal functors and coherence" [1,2,3,4].

- [1] https://mathstodon.xyz/@nilesjohnson/110741323263984146

- [2] https://mathstodon.xyz/@nilesjohnson/110876487813747736

- [3] https://mathstodon.xyz/@nilesjohnson/110979458364785667

- [4] https://mathstodon.xyz/@nilesjohnson/111070640771166081

Our neighbor painted this for us when our cat died a couple of years ago, and it captures his temperament so well I almost can't bear it. He's a great companion for this little thread though.

Example

Here's our first example! Suppose f: A → A' is a braided monoidal functor, between braided monoidal categories, and suppose you want to know if the pictured diagram commutes. Here, the monoidal structures are denoted + and ·, f₂ is the monoidal constraint of f, and β denotes the braid isomorphisms in A and A'.

Our methods give a systematic way of replacing the monoidal and unit constraints with identities! The new diagram (next toot) is called the dissolution of the original one.

Our main application is that commutativity of the dissolution diagram implies commutativity of the original diagram. That's the slogan form of our coherence theorem.

[Note: in this thread, and in the entire paper, we restrict to strong monoidal functors. That's the pseudo part of pseudomorphism, and it's a really important restriction that I'm just going to gloss over here. Our introduction has a subsection about the relevant subtleties.]

[Note 2: Pros will see how to use naturality of f₂ and β to immediately determine that the original diagram commutes. The point here is to have a systematic approach that works for any formal diagram.]

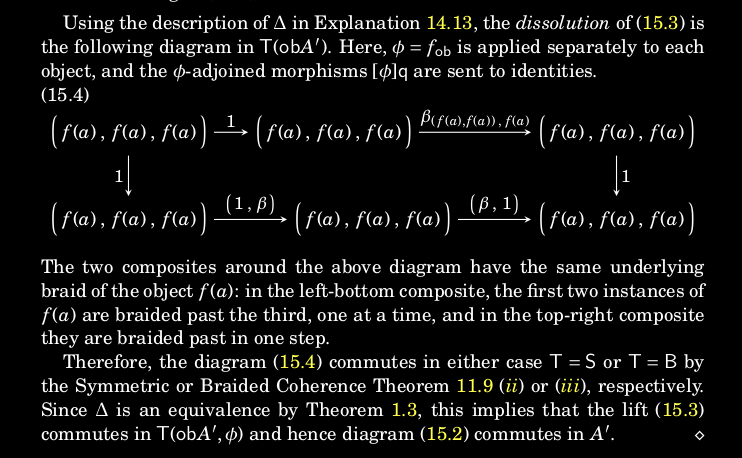

Screenshot of diagram (15.2). It's a rectangle with upper left corner f(a)·f(a)·f(a) and lower right corner f(a+a+a). The morphisms around the rectangle are two different combinations of monoidal constraints and symmetries that permute the individual terms a and/or f(a).

Here's the dissolution of the previous diagram (15.2). Here, T is the 2-monad for braided monoidal categories, so T(ob A') is the free braided monoidal category on the objects of A'. The morphisms β are formal braidings, the 3-tuples of objects f(a) are formal products, and… that's all there is to this diagram! It commutes because the two composites around the boundary have the same underlying braid.

💡 If you think the dissolution diagram looks simpler, because a bunch of generally nontrivial data is replaced with identities, you're right!

💡 And if you think it looks like a diagram that is completely different from the original diagram, you're also right! (But read on.)

Screenshot of diagram (15.4). It's a rectangle with the same shape as (15.2), but the objects have been replaced by the same one: a 3-tuple

( f(a), f(a), f(a) ).

The monoidal constraints are replaced by identities, and the various braid isomorphisms have been replaced by corresponding braidings of the entries f(a).

Two observations and another example

There are two weird and surprising things about our main applications.

🤔 First, the monoidal constraints of f could have nontrivial braidings, so replacing them with identities sounds like forgetting nontrivial data. It is!

🤔 Second, the monoidal constraints of f generally have domain/codomain that are NOT EQUAL. So, there IS NOT an identity morphism between them; we also have to swap out objects, and that sounds complicated. It isn't!

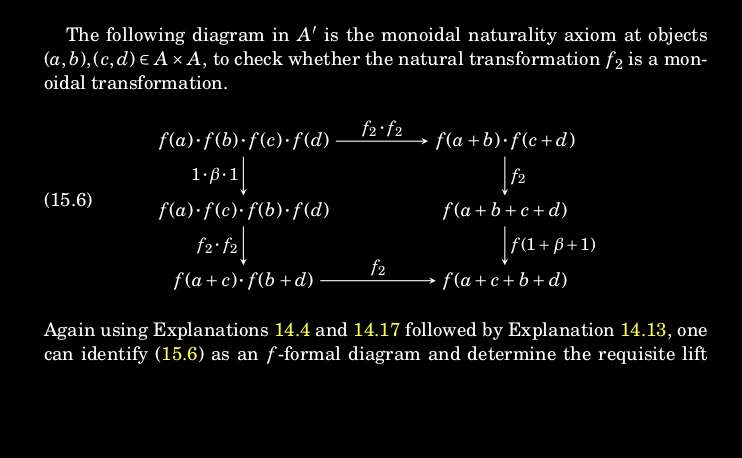

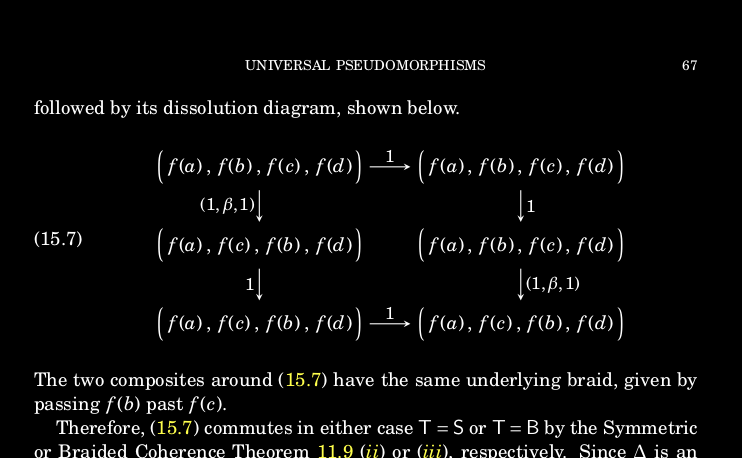

Here's another example! 🧙♂️🔮 The first diagram has some potentially nontrivial monoidal constraints, and the second one is its dissolution diagram. There, the only non-identity morphisms are two instances of (1,β,1), swapping the middle two entries of the 4-tuple (f(a), f(b), f(c), f(d)). There's just one of these in each composite, so the second diagram commutes. By our main theorem, this implies that the first diagram commutes too!

[Note: the first diagram is the one showing that f₂ is a monoidal transformation. I think it's wild that one can check an axiom about structure for f₂ by just discarding f₂. That doesn't usually happen.]

Screenshots of diagrams (15.6) and (15.7). They're both rectangles, and the former has various combinations of f₂ and β, but the latter has only the two instances if (1,β,1) and bunch of identities.

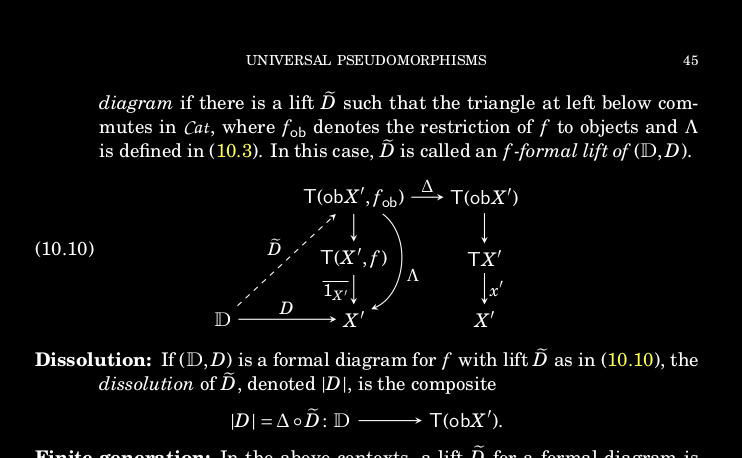

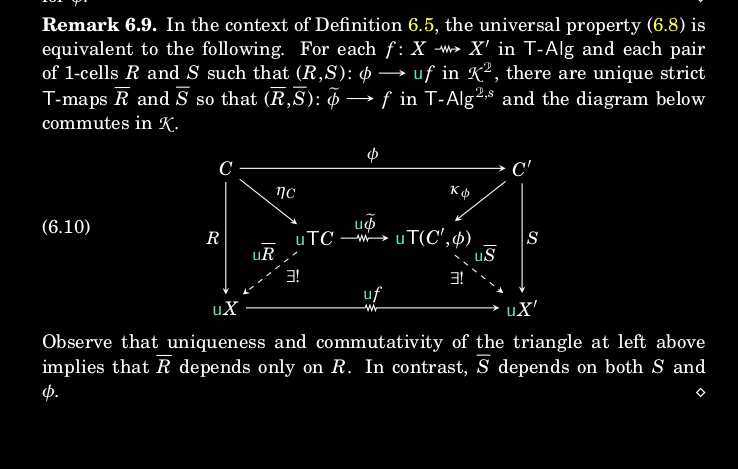

So, here's how it works. First, this only applies to formal diagrams—ones that involve the structure morphisms of a braided monoidal category or braided monoidal functor. In the screenshot here, a diagram

D: 𝔻 → X'

is formal if it lifts against the functor Λ. The domain of Λ is the codomain of what we call a "universal pseudomorphism", and it is freely generated by objects and structure morphisms for a T-algebra X' and a T-pseudomorphism

f: X → X'

(e.g., braidings and monoidal/unit constraints in the braided monoidal case).

The key to dissolution is the morphism Δ across the top. It's a (strict) morphism of T-algebras and it's codomain is a free T-algebra on a set of objects. Notably, it sends all formal monoidal constraints to identities.

Our main theorem gives some general conditions that guarantee Δ is an equivalence of T-algebras. So, if applying Δ yields a commutative diagram, then the original diagram must have also been commutative. That's the key idea!

The morphism Δ "dissolves" a formal diagram by distributing f into all of the products of objects, which are identified by the dashed lift against Λ. That's how the object swapping works, and then Δ replaces the monoidal and unit constraints (also identified via the lift against Λ) with identities.

So, that's why the dissolution diagrams can be so different. And yet, when Δ is an equivalence, the dissolution diagram commutes if and only if the lift against Λ commutes.

Screenshot of diagram (10.10). The key features are

Λ: T(ob X',fob) → X'

and

Δ: T(ob X',fob) → T(ob X').

There's an unfortunate page break here, and the word "diagram" at the top is part of the term "formal diagram" being defined.

Here's one way to think about it: In each particular formal diagram, some application of naturality and other axioms allows one to separate the diagram into a first part that commutes by axioms for f, and a second part that depends on axioms for T-algebras. Applying Δ is a way of filtering out the first part, which is always going to work out, and reducing down to the second part!

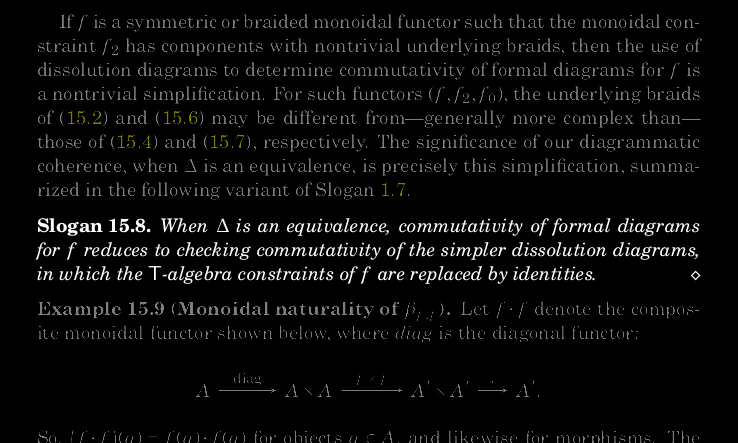

This is the slogan version of our applications:

💥 When Δ is an equivalence, commutativity of a formal diagram for f reduces to checking commutativity of the simpler dissolution diagram, in which the T-algebra constraints of f are replaced by identities. 💥

There are a couple more examples in the paper, and one cool (slightly cursed) non-example that I'll describe below. But first, I'll say just a little about the necessary conditions to prove that Δ is an equivalence.

Main theorems

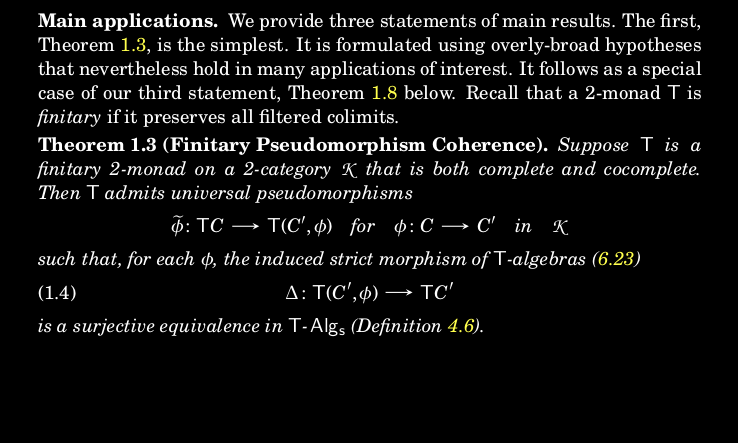

Here are the two main theorems. The first (1.3) just assumes that T is finitary and the underlying 2-category K is bicomplete. This holds in basically all the examples we know, including all of the monoidal examples. The second (1.8) is way more technical, and it shows the individual pieces that we actually prove. This is just here in case you want to know what kind of 2-monad theory you can learn in this paper; I don't think I'll try to explain any of it here unless someone asks 😅🫥.

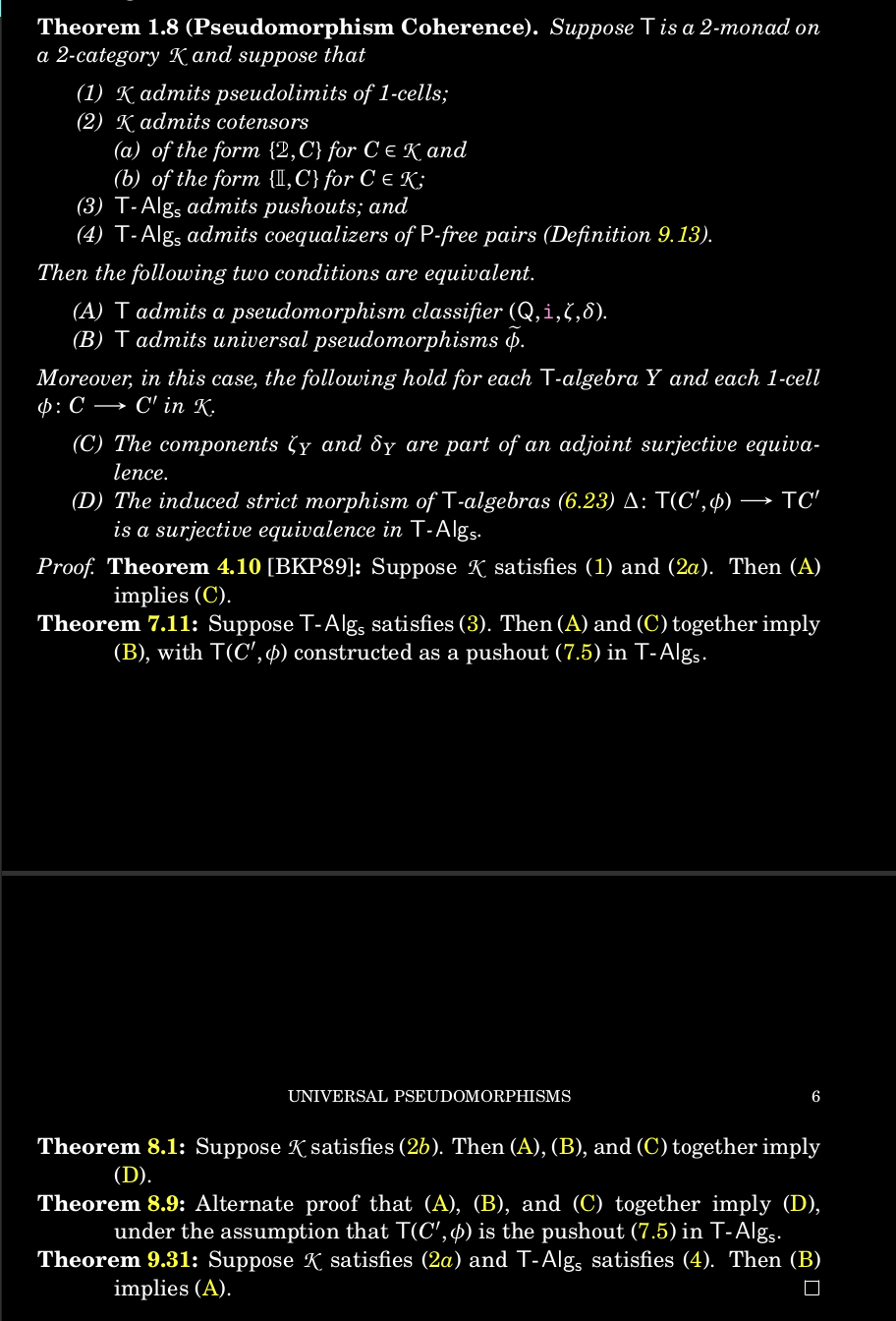

The key construction is a universal pseudomorphism ̃ϕ, freely generated from a plain morphism ϕ in the underlying 2-category K. It has the following universal property with respect to arbitrary pseudomorphisms f: X → X'.

🌌 Universal Property 🌌

Given a pseudomorphism f together with underlying morphisms R and S, there are unique strict T-morphisms, R̅ and S̅, so that the diagram commutes.

If T admits a universal pseudomorphism construction (UPC), then there is a universal structure morphism

Δ: T(C',ϕ) → TC'

for any morphism ϕ: C → C' in the underlying 2-category K.

The technical 2-monad theory in the middle of the paper is about (a) conditions under which T admits a UPC, and (b) further conditions to guarantee that Δ is an equivalence of T-algebras.

Screenshot of diagram (6.10). The outer boundary is a rectangle with ϕ along the top, uf along the bottom, R and S on the two sides. The universal ̃ϕ is an arrow in the middle, and there are unique dashed arrows R̅ and S̅ that make a commuting trapezoid with ̃ϕ and f. (The forgetful u is applied to all of them, for the sake of the rest of the diagram in K.)

Now, you may have recognized this universal pseudomorphism construction as a fancied up and generalized version of an argument from Joyal-Street [1]. If so, please let me know because you deserve a prize*!! Although that paper is famously about braided monoidal categories, they use a proto-version of our argument to construct their strictification of a plain monoidal functor. Their proof almost fits on the one page shown here, and their functor Δ is a special case of ours. Their work doesn't treat coherence for braided monoidal functors, but that's ok, because we have it now :)

[1] Joyal-Street, Braided tensor categories, 1993. https://dx.doi.org/10.1006/aima.1993.1055

(*) Super-fans of Gurski's work may also recognize Δ from another source. You also get a prize!!! The prizes are my admiration and respect. If you recognize Δ from yet a different source, please tell me that too, because I don't know of any more.

![Screenshot from Joyal-Street [1] page 31, showing their Theorem 1.7 (Coherence for Tensor Functors) about a functor Δ being an equivalence.](img/joyal-street-p31.png)

Screenshot from Joyal-Street [1] page 31, showing their Theorem 1.7 (Coherence for Tensor Functors) about a functor Δ being an equivalence.

Our treatment is a little more general than that of Joyal-Street; it applies to general 2-monads that satisfy mild assumptions about how they interact with co/limits. Our treatment is also a little longer, roughly the middle 1/3 of the paper. We use some pretty cool stuff from Blackwell-Kelly-Power [1], explained with a little more detail so we can understand the applications.

The key technical tool is the pseudomorphism classifier, Q, for a 2-monad T. It's a structure that doesn't have a 1-dimensional analogue, and it's a way of converting pseudomorphisms for T into strict T-morphisms. (Q is left adjoint to the inclusion of strict morphisms among pseudomorphisms.)

It's basically like a laser dance party 🪩 because it has a lot to do with coherence. 🔫 The key insight of the paper is that T admitting a UPC (toot 8 above) is equivalent (under some hypotheses) to T admitting a pseudomorphism classifier.

[1] BKP, Two-dimensional monad theory (1989). https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-4049(89)90160-6

Stock image of laser dance party with multicolored lasers over a hazy purple background. Silhouetted ravers in the foreground have their hands in the air, as if celebrating a good coherence theorem. Image from pixabay.

Final (non-)example

I promised to give a cursed non-example, and here it is! You might recognize some similar themes with my rants over the past few months, but this is new (to us).

For setup, let h: A → A denote the quadrupling functor h(a) = a + a + a + a for a ∈ A. This is a monoidal functor, with monoidal constraints given via the braiding β. It's not generally a braided monoidal functor, when A is merely braided, but it is a symmetric monoidal functor, when A is symmetric monoidal.

I think this is already pretty weird, but we had an even weirder idea: Consider the natural transformation γ: h → h given by the cyclic braiding of the first summand, a, past the other three, a+a+a.

🌩️😈⁉️ Is γ a monoidal transformation ⁉️😈🌩️

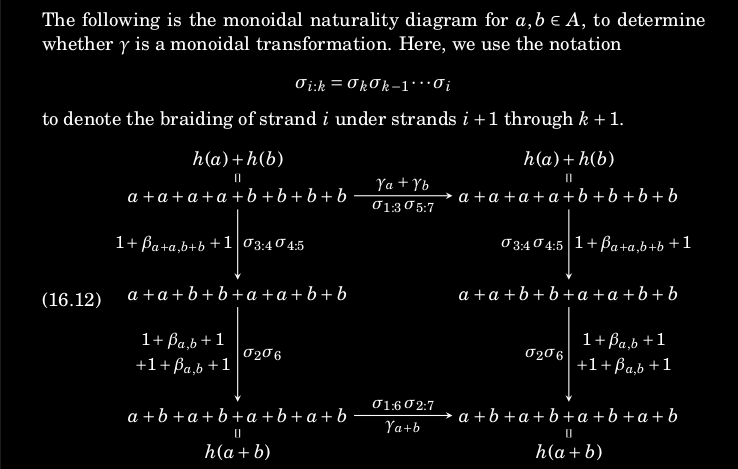

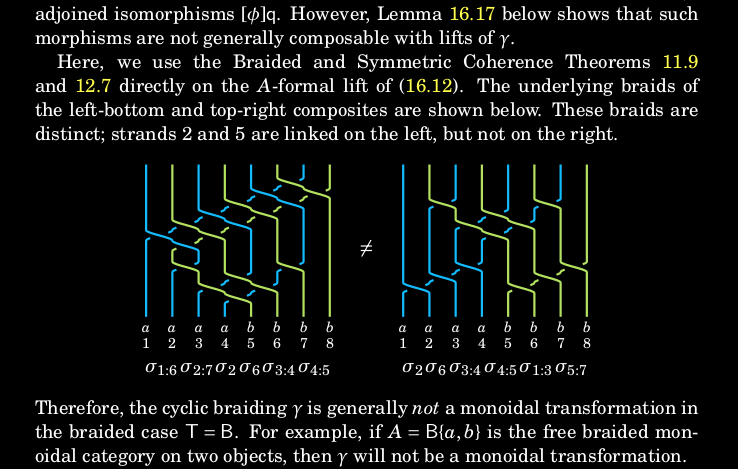

The attached pictures show the diagram that needs to be checked, along with their underlying braids.

p.s. The braid diagrams here and elsewhere are drawn with the amazing braids tikz library [1] by Andrew Stacey (@[email protected]). I really like this library :)

[1] https://github.com/loopspace/braids

Screenshot of diagram (16.12). It's a rectangle with upper left corner a+a+a+a + b+b+b+b and lower right corner a+b + a+b + a+b + a+b. The two composites around the diagram are described by a bunch of braidings drawn in the next picture.

Screenshot of the braid diagram for (16.12). Each braid has eight strands, labeled by four copies of an object a, and four copies of an object b. The two braids interleave the copies of a and b in ways that are almost the same, but one of them has an extra linking of strands 2 and 5.

In the previous toot, the braids are not equal, but their underlying permutations are equal!! This means that γ is a monoidal transformation when T is the 2-monad for symmetric monoidal categories. On the other hand, if A is merely braided monoidal, then h is a monoidal functor but γ is not a monoidal transformation.

Here's why this is a non-example of our stuff: For this diagram, we can't check commutativity by ignoring the monoidal constraints h₂ and replacing them with identities!

Even though (16.12) is a diagram consisting of only braidings, and therefore is a formal diagram for A, it is NOT a (nontrivial*) formal diagram for h. The diagram (16.12) lifts to the free algebra T(ob A), but, going back to our formalism of dissolution diagrams, it has NO nontrivial(*) lift through Λ: T(A,hob) → A. So, it doesn't have a dissolution diagram to simplify the calculation.

(*) The word 'nontrivial' is doing a lot of work here, and I'm skipping some serious technicalities to emphasize the key features. See Lemma 16.17 of the paper for precise statements.

The problem in the previous toot is, basically, that the odd permutation underlying γ interferes too much with the monoidal constraints h₂. I mean, γ is "compatible" with h₂ in the sense that the diagram commutes (when A is symmetric monoidal). But one can only see that the diagram commutes after "unpacking" h₂ in terms of braid isomorphisms β. In the other examples, one can just use formal monoidal constraints, and ignore their underlying braids. That's why the dissolution strategy works for those, but not for γ.

That's what I think is so cool, and slightly cursed, about this (non-)example! It shows that our main applications do have limits, but it also shows just how weird those limits are. In more reasonable situations, like the earlier examples, the dissolution strategy is a useful simplification.

Thanks!

Thanks for taking a look at this! If you're interested in hearing more, or if you have questions, ask me 🙋😃 You can also check out the paper which, y'know, has a lot more stuff in it. 🪅 🎊 🎊

https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11261

(14/14)

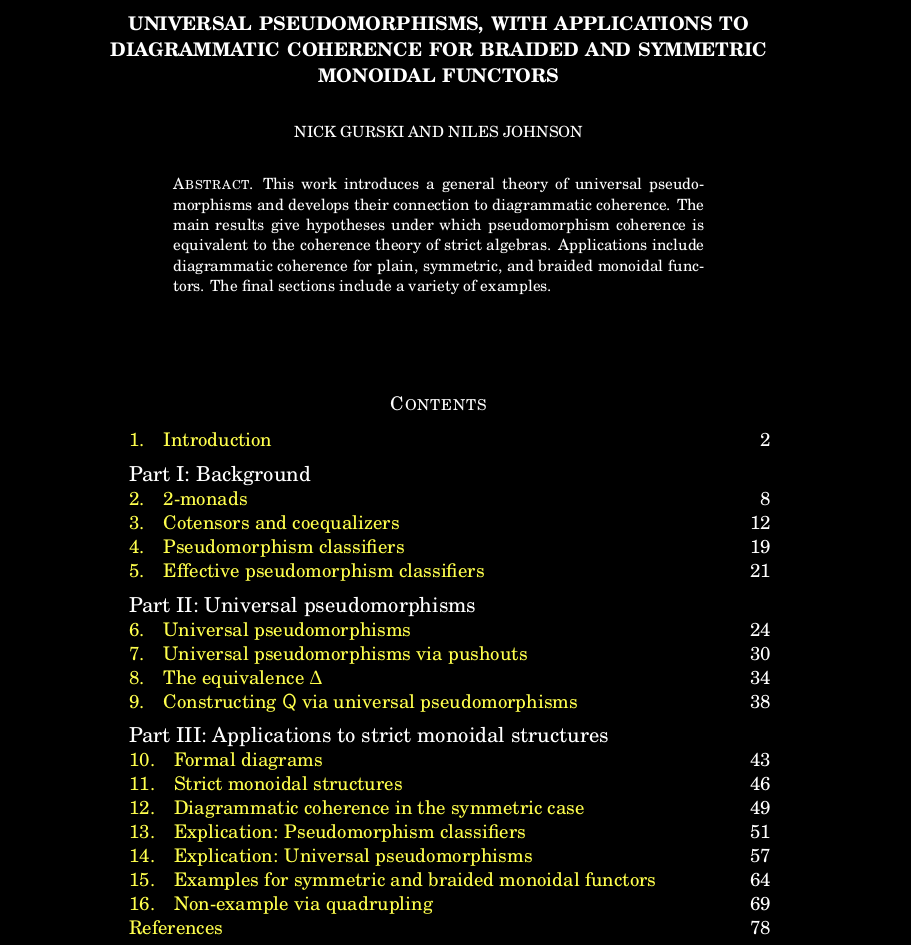

Screenshot of title page with table of contents showing 16 sections spanning 77 pages. The paper is divided into three parts:

I: Background

II: Universal pseudomorphisms

III: Applications to strict monoidal categories